FRED THOMPSON

FRED THOMPSON

Financial success, reputational success that you spend your entire life. And in fact, you're, you're supposed to look out for you or yourself and your family, you're supposed to work as hard as you can to be successful, to dare. I say it to win. How do you square that with being a good person? How do you square that with living a life where your ego? It's not the center of everything.

RODNEY LEE ROGERS

Welcome to the pure theater podcast. I'm Rodney Lee Rogers, your host. And that was Fred Thompson, playwright of Atwater our conversation for today. Well, this is podcast number one. It's been about seven years in the making, but what we want this podcast to be is conversations around what we do at pure with the artists and designers and just all around amazing people that we come across.

This being our very first episode, I have a special surprise for anybody who makes it all the way to the end. So be sure to hold on for that very special opportunity. Fred Thompson and I were able to catch up at the very tail end of our production of Atwater. Atwater was a pure theater world premiere, which means as a company we take the play from creation to production.

it really was, uh, an incredible experience. The audiences were amazing, and it's a play that will definitely have a life well beyond its first production. Atwater chronicles mainly the afterlife of Lee Atwater. If you're not familiar with Lee Atwater, he really was the grand architect of devisive politics.

There's a great documentary you can check out on Frontline for his life in reality. But as for his life in the play, let's listen in to our conversation with Fred Thompson.

RODNEY LEE ROGERS

So we're talking politics, and what kind of fascinates me about Atwater is the politics of it. Yeah. And politics and theater, because some people will have you think, and I think we're also in a time right now where theater is more political than it has been probably over the last 25, 30 years. And what the difference between political theater and regular theater, and what's satire. How would you categorize this play? To me it seems like satire. What would you categorize?

FRED THOMPSON

I would say that This play started as a fairly humorless examination of Lee Atwater having judgment being called to account for his life and attitudes. On the terms that he actually set out in his final days, he actually set out to try to make an accounting of his life and to set things right in a sort of a theological way.

And it started out as that, but it very quickly, I realized that I didn't really care that much about Lee Atwater and his life, but that I cared an enormous amount about the question. And that is. In a complex society that we live in, where there, every reward that you can possibly look for is based on ego, ambition, financial success, reputational success, that you spend your entire life, and in fact, you're supposed to look out for yourself and your family.

You're supposed to work as hard as you can to be successful. So, uh, dare I say it to win, how do you square that with being a good person? How do you square that with living a life where your ego is not the center of everything? And I, I am endlessly fascinated and wrestle with that thought and I don't have an answer to it, but that was, you know, that's what I hope comes through.

Well, once you say it that way. Then all of a sudden you end up, you run that down, you go back and forth, back and forth, back and forth a little bit. And you realize how absurd it is. There is an absurdity in the world that we are in that cannot be reconciled by a, by a single force of will. Now, you can do that, and there are people who do that.

They reduce their lives to a single idea, and they go forward. But if you're living in a Complex world. If you're living in a, dare I say it, a chaotic world where there are all of these political, social, interpersonal, cultural dynamics that are going on, and you're sort of swimming in it. How in the world do you try to be a good person in that world?

And the image that comes to mind is. It's absurdity and that makes it, I hate to say it, but it makes it funny. And so very quickly, it's clear to me that it has to be funny. It has to be. The only way to deal with it. Is to invoke a sense of humor about it because we really are, we find ourselves in an absurd place.

So, there you go. That's, it's, it's, it's, it's, it's, I don't think it's satire. I think it's just an absurd humor.

RODNEY LEE ROGERS

The winning part is what comes across to me strongest. Because it's like every time that that's uttered, and I think at one point he says, but I won, it's like the, the just sheer misunderstanding that that's not the ultimate goal.

And certainly when we're talking about a higher existence, winning isn't. And yet we, there's so much, there's so much in there. He, the fighting, all of it, you know, not to give away the, the play, but it's like. He's still trying to win his way in and I think, do you think, and that's my, do you think that's a uniquely American? I mean, do you, it's, it seems like it's ingrained.

FRED THOMPSON

Well, you know, I, I, I watched the British baking show. Yeah. And one of the reasons I love the British baking show is that every one of the participants has this self deprecatory way of being and they're, they, it's clear. That their culture requires or allows.

A degree of humbleness that in America, you know, I'm sure that there are places where people are humble and I'm sure that there are places where people are self deprecating, but every place I generally have been where. You know, there is a, a lot going on the, the necessity of self promotion of ringing humility out of your persona and being full of chutzpah is always essential to getting where.

You think you'll, you want to get if you, if you are, you know, if you keep your candle under a bush, you don't, nobody will come knocking, you know, you write the perfect screenplay and you put it on your shelf. It will never, ever get read by anybody. Nobody will ever read it. Yeah.

RODNEY LEE ROGERS

And that particular business, having been through it, self deprecation is. Death. Well, it's like the minute you, you are actually self deprecating.

FRED THOMPSON

Although the problem with self deprecation and I, Carolyn will roll her eyes when she hears this, because I say it all the time. The problem with self deprecation is. Unless you're somebody like Ronald Reagan or Thomas Jefferson, where the person who's hearing you be self deprecating, unless they know that you really don't mean it, unless they know that you really do think that you're the smartest guy in the room, the problem is they actually will. We'll say, Oh yeah, he's pretty bad. Oh yeah, it's too bad that he's, that he's so mediocre. You know, the problem with self deprecation is people will believe it. They'll immediately step, step on it. And that's, there's so little authentic self deprecation. The only way you get, you're allowed it is if you are. Yeah, once you get to be successful, then you can be George Clooney. Yeah. And make fun of yourself falling down. You can do all sorts of stuff. Yeah. Once you get there, I imagine Tom Hanks could come in and just get just wax poetic about how, how foible, you know, how he has all these, but nobody who has not already gotten to that position, we got onto the subject because you asked, was it an essentially American thing? I'm afraid it is. I mean, I went to Canada. It's the strangest thing. I happened to be there the night of the elections of their prime minister. And so I'm sitting in Toronto and I turn on the TV and there is the leader of the leaders of the two opposition parties. And they're on the same TV show. They're sitting side by side, and they're chatting about what this means in terms of policy and about how they hope to do this and they want to do that and you can watch and you can see these guys actually know each other. They have a high degree of respect for each other, and that's their culture. You know, that's the culture that they come from. We used to have that in this country back in the Tip O'Neill days. You know, the Robert Dole days, there really was this reaching across the aisle. And I think it's hard to, to, to know the extent to which social media drove it or social media just recognized it, but there's no doubt that it lit a match to this bell jarring of America.I mean, now you find your posse, you find your group and you huddle up. And you view everything through the interest of your group, even to the point where if your guy is a terrible person or your guy does terrible things, he's still your guy. And you know, the, the, the obvious example you want to talk about is Trump, but we saw it with, with Clinton. I never will forget back in 1998, sitting there going, dog gone it. I have to go and defend Clinton for standing in the hallway of the oval office. Because he's my guy. I mean, what, why do I have to do that? You know, you see, you see that on both sides is that you have to pick a side and it's your side better for better for worse than you view everything. Through the prism of that interest and it, it, it helps to view the other side as terrible people as demonic. It helps to view Putin as a better American than a Democrat, which I've never have understood that. But you go, where does that come from? Yeah. Yeah. Anyway. And so it finds its way into play.

RODNEY LEE ROGERS

I do want to ask you about. Theater. Like, what would you say your relationship to theater is? How did you come to this? Like What does theater do for you?

FRED THOMPSON

You know, I, my background certainly has nothing to do with the board art. I was an extra in a play like 25, 30 years ago with Julian Wilde in Twelfth Night. And I, I was an extra, I was a, a, a, a gang member. He had envisioned Twelfth Night as being a, a, uh, 1930s gangster movie, uh, or, or play. And so I was, I was sort of a, a gang member and sat around. I didn't have a, I didn't have a speaking part and I had to laugh at myself because I said, I'm never going to be in another play unless they give me a line, you know, uh, And so it was, it was a fascinating and interesting experience, but I never built on it and it really wasn't until I started.

And I think if I had just gone to the Charleston stage and watched these Broadway musicals, I would have never done anything. But the pure theater, when it was over on King street, I started going to those plays and they were fascinating. That here's this, it's almost like, I don't want to say it's like it is, it's like poetry because nothing is. Nothing is as bad as poetry in terms of not having a popular value or a monetizing

I mean, to me, I'm, I, and I have been poetry for my whole adult life. And that's one of the beauties of it is that there's absolutely, well, people are starting to try to figure out a way to quote monetize that. But for most of my adult life.It had no commercial value at all. I mean, you take the biggest poets in America, Wendell Bailey, Barry, and they, if you saw the money that they made, they made like 20, 000 a year. I mean, he really was a farmer. He really was a school teacher. Because it had no value. And that made it so wonderful. The serious theater is almost like that.

RODNEY LEE ROGERS

It's very close.

FRED THOMPSON

There's not much appetite for it in America. And that had a huge amount of appeal to me. And I saw like five or six plays. theater and they were all riveting and they were all stunning. And so I just liked it a lot, but this play, you know, I, I was born in 51 as was Lee Atwater same year.

So we actually, if he was alive today, he would be exactly my age. So we've lived through the same. The same time period in South Carolina. And I was very familiar with his career and I was very familiar. I actually had, I remember when the life magazine article came out in 90, 90, 90, I guess, 90 with his, with his, his, his forgiveness, his, his redemption.

And it was always fascinating to me. And I also was always fascinated by the fact that none of his disciples took him to heart. I mean, none of them said, you know, he's right. I'm going to do better. Oh, he's right. I'm going to live my life differently. They all just kept right on trucking, which always fascinated me.

And that always made it a complex thing. And then I think I've already told this story once before. Pure did a online. Auction is a fundraiser. This is about seven, eight years ago. And one of the lines was you could write a 15 minute play. And direct it yourself and the pure players will act it out and we'll do it on the pure stage.

And nobody had signed up for it. Nobody bid on it at all. So I, purely to keep it from being an empty line item, I says, well I'll go ahead and make a little bid. So I bid on like Monday and it was like 100. And I get a call on Saturday saying, you won. And I hooted. I said, Sharon Gracie. And Roddy Rodgers to bust, just be shaking their heads that they have to show up with two or three pure core members and they have to put on some sort of crappy amateur play for a hundred dollars and I laughed and I never called him in on it because it was so funny, but I did know what I wanted to do and that what, what the 10 minute skit was going to be would be Lee Atwater meeting me.

St. Peter. Yeah. And so I actually started writing it out and writing it out and about two years ago I had got to the point where I had the, I got to one point and it was like 28 pages and then I got to another point it was like 42 pages and I got to another and it finally ended up being. A full length, and that's when I let you read it.

Yeah. And that's when the, the, sort of the theater lab, we started doing table readings and some things worked and some things didn't. And it flowed, and I think it flows nicely. Oh yeah. I mean, I got no idea what the audience

RODNEY LEE ROGERS

They're loving it. I mean, so we're, we're two weeks in, you know, the, the houses have been good. They laugh all the way through. And I think they come out, it's that experience I think when somebody comes out of a piece and they have. It not only makes them laugh, but makes them think. And I think it's been, it's been extraordinary. What, how great we got, what we got out of that. I don't even remember that.

Like, that's what's interesting. I don't even remember. So I guess when you didn't call it in, we even did it.

FRED THOMPSON

You know, the world is full of plays that closed on Opening night and nobody knew how bad it was. Well, I, I, I'm, I'm relieved that it, uh, I knew early on that it was not going to be mediocre, that it was either going to be well received and it was going to be good.

Or it was going to be a total fiasco and either way was going to be fine with me. I mean, when you're 71, what good is a successful play or what is the difference between a successful play and a fiasco? There is not as, but it's still, it's the same experience.

But I will say the, I think that the, and the name, the, the cultural wars are so great. Everybody's wearing their blue hat and their red hat that there will be people who will just say, Oh yeah, I know what this is about. This is a hit job on Atwater. Right. And I'm mad about mad about it. Well, I hope they're not.

I hope that. People will see that this is a, this is a very sympathetic look at a soul swimming in a chaotic world. And like I say, I kind of like his story, but I'm obsessed with my own soul. I'm obsessed with what do I do? Where do I, how do I do better? How do I do good? Or how do I know I'm not a terrible person?

I mean, all those things. Are things that we all confront and we all wrestle with, and it sure does help, you know, it helps a lot to laugh while you're doing it. Absolutely.

RODNEY LEE ROGERS

Well, and I think that it's like the show itself. I mean, it's, it's, you remove it, you put it 500 years, you take this out. Well, I don't, who knows what we'll be in 500 years, but you put it a hundred years where nobody knows who Atwater is and it's. Almost Shakespearean. Like, it's like, it's, it's a quasi tragic figure facing their life. And I don't think it is all, it is at all. I'm always amazed how he comes off. And we were talking about how that self deprecation is, has become almost a charm to those who are, you know, kingly ones. And it really comes off in this.

And I'm sure he was incredibly charming, uh, human being, the way to get through what he got through. But I really think what the play does is it asks the questions you're talking about versus was this a worthy life or not worthy life is what does it mean to go through this. And I think that's the real power of it.

And that's all, that's what we're interested in. You know, we're not interested in, in putting on the blue hat or the red hat or the, you know, we're interested in, in how a human being and in this particular case, how a soul goes through this kind of life. And, you know, that being said, it's like, How it comes at you is just.

Fun for lack of a better word. It's just a fun way to kind of introduce those issues, but they're all so very much there.

FRED THOMPSON

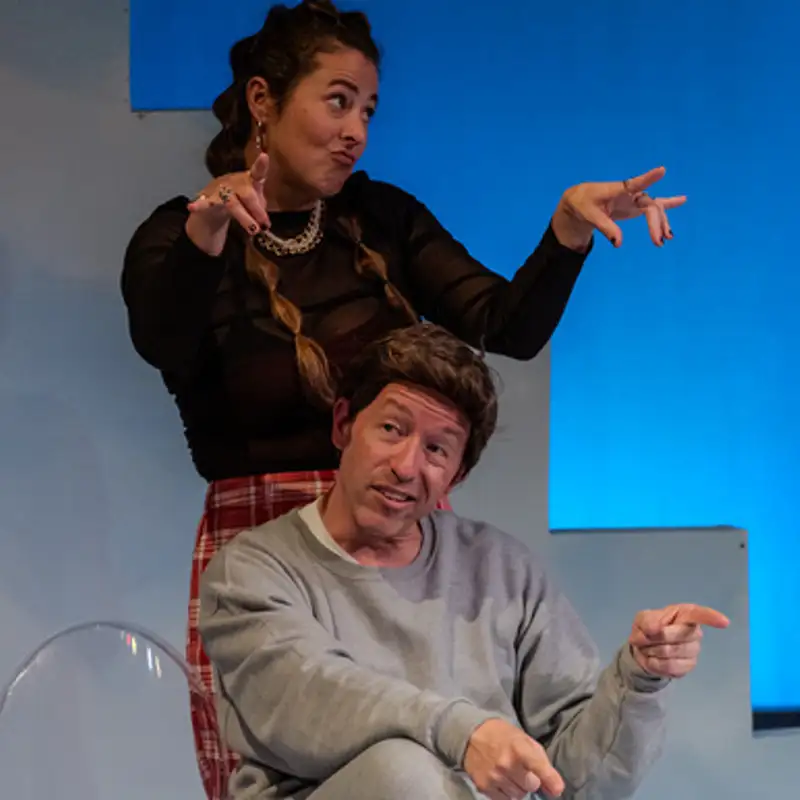

Now, the one thing that I will say, I wrote these words and I know what the words were supposed to mean, but these three guys, joy and Brandon and, uh, Camille, they have made these characters into real.

Living creatures, and they've added a dimension that the cold words really don't have. And it's, they've just, it's, I'm sort of in awe of these players. They really are, are good, and they're, they're pulling out dimensions that I didn't put in there. Maybe they were there, but I sure didn't see it.

RODNEY LEE ROGERS

That's the, that's the beauty of theater.

I mean, you're taking words, you know, that have been, you know, basically your thoughts and ideas that have been put into words, and then you're unlocking them, and how they get unlocked through the group. Yeah. is how they come alive. As a playwright, you've always got to let it go once it goes to that production.

Because at some point, that actor is going to know more about that character than even the writer. Because when it gets out there in life, that becomes part of them. And I think these three are uniquely, what they bring has really been a lot, but it's always the kernel of the exploration of what the ideas are.

And I think that's the real, like we were talking about, the strength of the piece is that idea for me. Of what it means to win, what it means to win in this society and does winning paper over, uh, a host of ills and bad behavior when it all comes down to it. So, yeah, I mean, I, I find the piece has incredible depth.

What's your idea of heaven? Like, what's your idea of what's next?

FRED THOMPSON

Oh, you know, I, here again, the, there's the absurd is a, is a good place to have all these questions. You know, Nietzsche said that we're all doomed. Yeah. So let's party. I mean that he didn't use those words, but that's what he meant. He says, why are you so serious?

We're all doomed, you know, dance. I like to believe, and I do believe that there is a, some form of, of, of continuum. I sure don't think it's a corporeal spot, you know, like, you know, and I sure don't think there's a first circle of hell, although Dante makes that sort of like the place to be, but I do like to think that there is a, a continuing place for that, for that energy.

And if it's certainly, I embrace the myth. I choose, you know, it's a Walker Percy said, we'll live your life this way. And if you're wrong, you're still as well off as if you didn't. And if you're right, by golly, you're, you're lucky, you know?

RODNEY LEE ROGERS

So you've seen it a couple of times now. I know you have friends in town coming to see it tonight.

How much is it? Like, what was, first of all, what was the experience of watching it the first time?

FRED THOMPSON

The, the, the, well, I mean, the, the, the, the first time, if Sharon had not stood up and announced that it was a comedy, the first five minutes aren't funny. The first five minutes are like, it could be, it could be anything.

It'd be a tragedy. It could be a horror. There is a certain amount of horror. And so the crowd, even though they were given The instruction that it was funny, the crowds doesn't want to know what they've got and you can feel that, but by the time that they get into it and they begin to realize that this interaction has some real absurdity to it, the crowd really warms up.

So I like that. I like the fact that you're playing a little trick on the audience at the beginning, or at least you're not, you're not hitting them over the head from, from, you know, your, your, your central character doesn't slip on a banana peel as he comes on stage. I like. You know, I like the, the slow reveal.

I also think, and this is totally unexpected, but the casting with gender and with race puts a, and it's completely unspoken. I mean, nobody ever remarks on it. I mean, this is, it's, it's not part of the. Not part of the play, but it's undeniably there and it's, it's, that's fascinating to me is that there is an undertone of seduction that if you read the script.

I can tell you for a fact, the author didn't put it in there, but there it is. And it's, that's fascinating to me. And that was actually unexpected when I went, I was going, Whoa, that's, that's interesting. And then the, well, I don't want to talk about specifics of the scenes, but Sharon clearly has a three dimensional vision.

That I don't share and she would say, Oh, we're going to do this. And I'd go, Ooh, and then I'd see it and I'd go, Oh yeah. I mean, every single thing she does makes it more vivid. And it's fascinating to watch that we're sitting there in a laboratory and we can actually turn and say, you know, let's cut this.

Let's cut this. This is a rant that nobody needs to hear. Let's chop it out. And we did that several times. And every time there was a deletion. It added to the play. That's one of those things that's, you know, they tell you, you cannot be your own editor because you love your words so much. And that's true.

But I can also say, every time you cut a word, it gets better. And that's, that's a, that's a truism.

RODNEY LEE ROGERS

I think that's the joy of the development. Oh, I hate that word development, but that's the joy of Doing a play that's coming to life as you work it. And for a playwright in the room, it's imperative to be there.

Because as those things go, you can have, you can go off, it can go in directions you don't want it to go. But when the whole team is there kind of shaping it, then it stays true to kind of what it is. And I think this has been a real testament to that. I think the show has really It's become the show that it is and, and wants to be versus a show that it's not. So you're seeing it again tonight?

FRED THOMPSON

Yeah.

RODNEY LEE ROGERS

Excited?

FRED THOMPSON

Uh, you know, I am intrigued by it. You could, you could watch the, the characters. Developing and interacting more and more, and that'll be interesting to see with three more, two more, three more performances where they've gone with it.

RODNEY LEE ROGERS

Thanks for joining us for our conversation with Fred Thompson, playwright of Lee Atwater. One of my favorite people and always a very interesting conversation, which is really the whole point of this entire podcast. What I've found through the conversations I've had so far is I learned so much more about the people who I thought I already knew.

Next up is R. W. Smith next week. You know him as Smitty, one of our original core ensemble members. Be sure to subscribe, like, favorite, whatever you do these days, and keep up with us on your favorite podcast platform. Now, I promised a surprise to anyone who hung in there till the very end, and here it is.

You can reach me anytime at rodney at puretheater. org. But if you write me this week, include in the title Streaming at water and I'll send you a streaming link to the play. Thanks again so much. Have a great week and we'll be here next week with R. W. Smith.